Publications

The shroud at the break of dawn

Madrid2025

Design: Mira Bernabeu

Writings: Laura VallĂ©s VĂlchez

Handout

Exhibition: The shroud at the break of dawn

Publication (PDF)

Writings

- The shroud at the break of dawn - Laura VallĂ©s VĂlchez

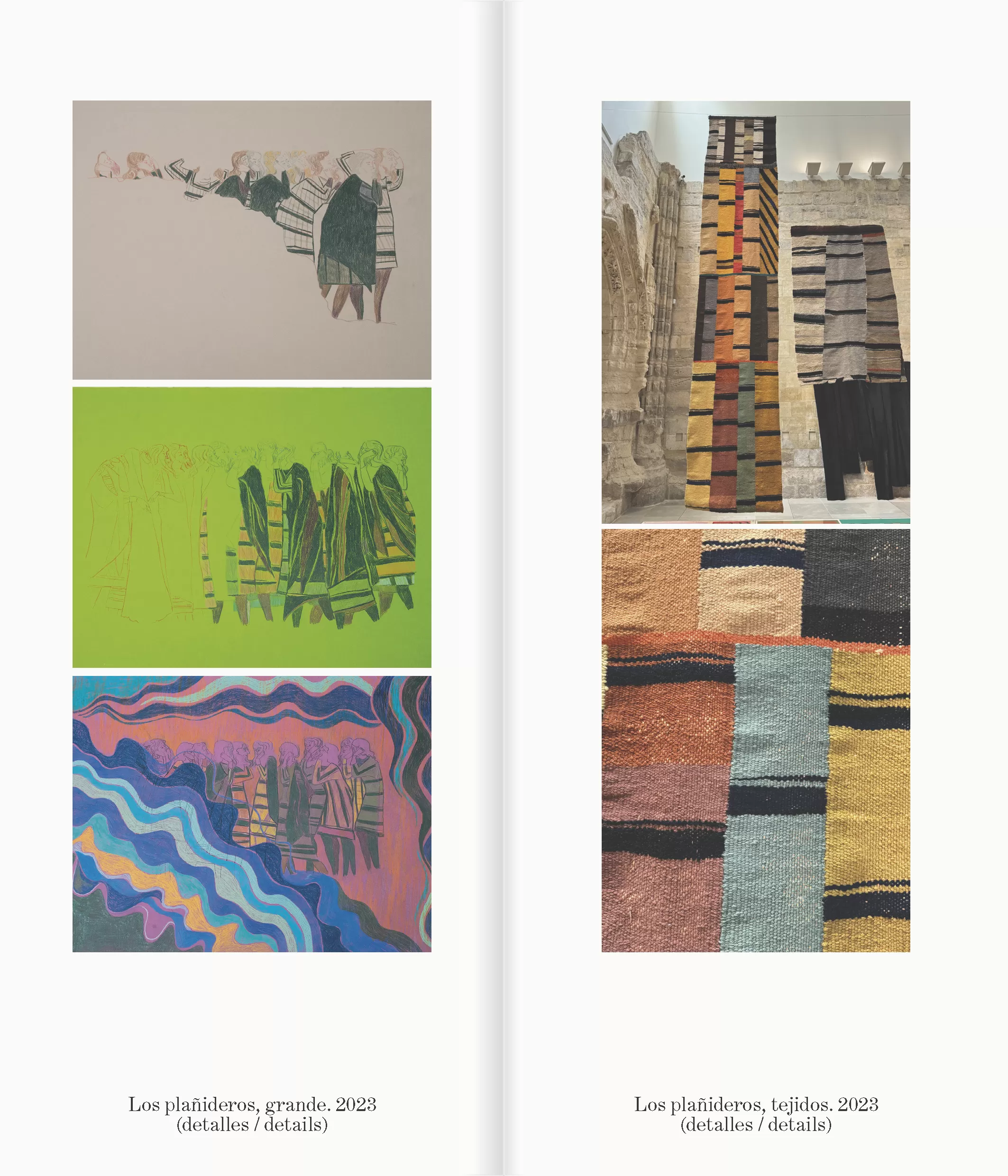

Night falls upon "us, the living," those of us who can hear and claim the voices of the disappeared as our own. Candles and torches are lit, their flickering light suffusing the air with a faint glow that dissolves the gloom. The firelight illuminates the darkness, transforming colours in its glimmer: the yellows of skirts meld with greys and deep browns, while hair takes on a reddish hue, reflecting something more profound than a mere shift in pigment.

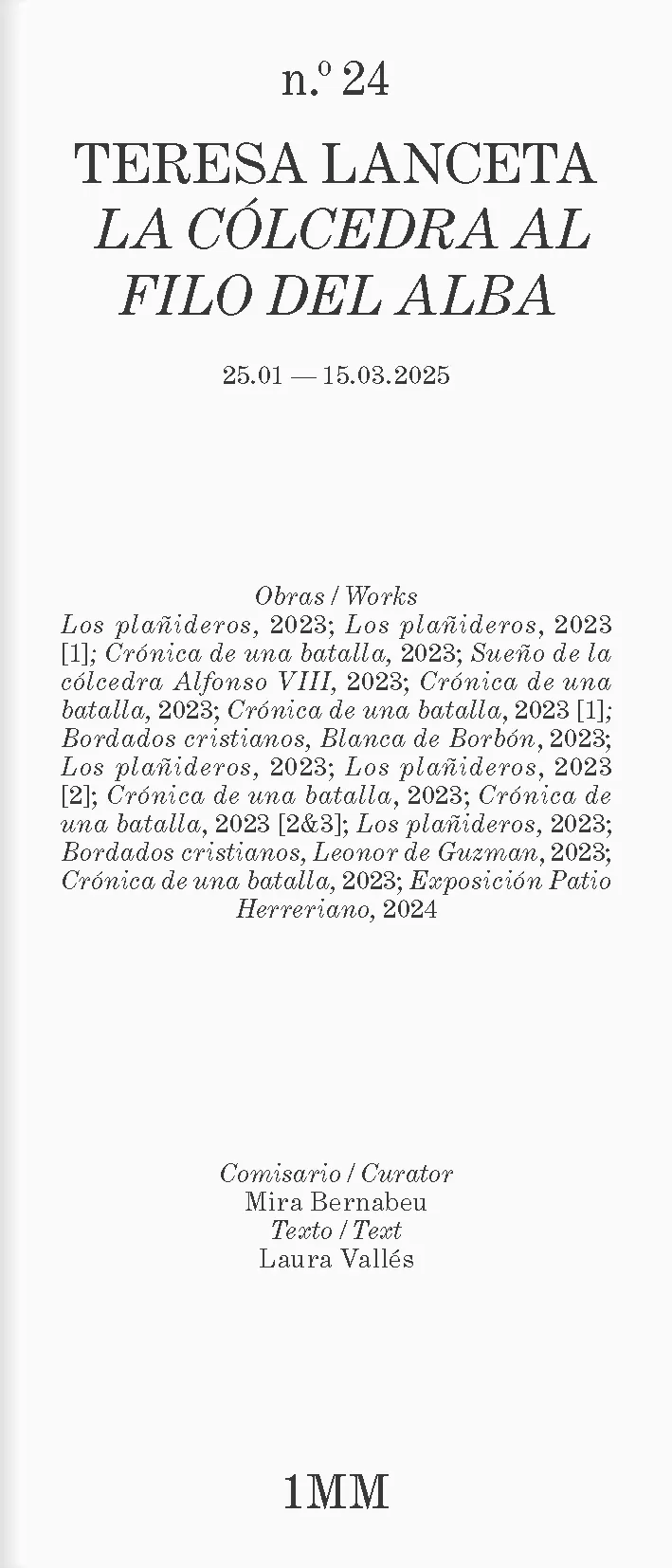

In this luminous atmosphere, the vigil unfolds not just as a ritual but as an experience that transcends it, becoming an echo that accompanies the stories of those who have departed, even now, in times of war. This chromatic interplay connects with the figures of mourners, seen in anonymous medieval depictions such as the 1295 painting preserved in the MNAC and reimagined by Teresa Lanceta. These mourners serve as symbols of collective grief. Common across medieval Europe, professional mourners were women hired to publicly weep and lament the loss of someone, giving a face and a voice to sorrow. Through their ritualised weeping, these figures—sometimes men as well—channelled emotions that the bereaved were unable—or unwilling—to express. Yet their role was not solely affective; it also carried cultural significance in a profoundly hierarchical society where death was both a personal and a public spectacle. In the delicate coloured-pencil drawings featured in this exhibition, these enactments dissolve and reassemble time and again, as though their image cannot be fixed in time. A similar phenomenon is observed in the battered, dismembered, or wounded bodies from the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212), a XXIII decisive conflict in the Reconquista that marked the decline of Almohad power on the Iberian Peninsula. The representation of suffering in this context confronts us with the ethics of representation—a path of engagement that Lanceta frequently explores. This clash between Christian and Muslim forces left behind not only corpses on the battlefield but also a legacy of suffering for women, many of whom were victims of violence and dispossession. In this framework, the curatorial becomes a tool that mediates these memories, creating a space where images and the artist's own oral storytelling engage in dialogue with voices from the past. Although these evocations dwell in the historical realm, they resonate with the present, a contemporary moment shaped by new forms of resistance that complicate any linear notion of time. In times of war, we know too well that women have often been rendered invisible. Here, however, they are reclaimed as protagonists through their narratives and experiences, which transcend centuries and take on new forms of expression. A chronicler of the everyday and a historian of forgotten details, Teresa Lanceta's practice is rooted in an approach that values the seemingly insignificant—the fragments of life often excluded from grand narratives. This mode of historiography is anchored in her experiences of camaraderie and revelry in Spain during the 1970s, a period of political and cultural transition under Franco’s dictatorship and in its aftermath. Tied to oral traditions and festive gatherings, this way of engaging with the “word” reflects a mode of knowledge transmission that exists outside the officialdom of academia. Instead, it emerges in conversations, songs, and shared gestures—closely aligned, in Lanceta's case, with the sensibilities of flamenco. From this perspective, the artist invites us to reconsider what we understand as history, shifting the focus to those invisible folds that position us, as an audience, to confront the pain of others.

Here, we hear her voice. Enter! You will hear a lament, a breath, a tentative movement toward something new. In this project, what we call “the contemporary” ceases to be linear and instead becomes a new temporal pattern, unfolding and folding into a dense temporality.

This dynamic is evident in the textiles that inspire part of the exhibition, where fabrics reveal a narrative that goes beyond their threads. One notable example is the Almohad Banner from the Monastery of Las Huelgas, a textile originally taken as war plunder but later transformed into an object rich with cultural and religious symbolism. This banner, crafted with advanced weaving techniques requiring immense skill, serves as a testament to the coexistence and conflict between Christian, Muslim, and Jewish cultures in the Iberian Peninsula. Its technical intricacy can be likened to contemporary open-source computational systems, where diverse influences and collaborations intertwine to create something new. Another significant element is the cólcedra, the funerary shroud that covered the body of Alfonso VIII and inspired three of Lanceta's artistic proposals in this exhibition. This Castilian king, a central figure in events like the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, was buried with a quilt that combined practicality with solemnity. The cólcedra, with its rhomboid quilting—simplified and reinterpreted by Lanceta—not only served a functional purpose but also symbolised death as a transition, enveloping the deceased in a final act of care.

The exhibition’s sonic dimension revives, through Lanceta's voice, the stories of women like Eleanor of England, Queen of Castile and wife of Alfonso VIII.Eleanor’s life was shaped by the political and familial tensions of her time. Founder of the Monastery of Las Huelgas, she was a patron of the arts whose wealth—despite the plundering that left her bereft of possessions—is reflected in objects like a silk pillow, whispering fragments of a life lived between two worlds. Similarly, the exhibition delves into the experiences of other women marked by violence, such as Leonor de Guzmán, one of the most powerful figures of her era, whose downfall after Alfonso XI's death epitomises the peril inherent in holding a prominent position in a court governed by passions and vendettas. Alongside her, the mother of Pedro I of Castile, María de Padilla and Blanca de Borbón—lover and wife—reveal other dimensions of this violence. María de Padilla, rigidly bound to the king, and Blanca, spurned and fatally poisoned, embody the conflicts of power and desire that characterised the medieval court. Though seemingly oppositional, these women share a fate dictated by the patriarchal structures of their time, which relegated them to secondary roles in official narratives. Questions like “What shall I do with my fear?”—stitched into Lanceta's works and reframed by poets such as Alejandra Pizarnik and Anne Sexton—become acts of memory. They create a space of vigil that invites us to reconsider our relationship with history.

This exhibition acts as the second chapter of an investigation launched in 2024 at the Museo Patio Herreriano with El sueño de la cólcedra, curated by Ángel Calvo Ulloa. Expanding its layers of meaning, this project situates the stories of these women within a broader historical, poetic, and social framework, posing a fundamental question: How can we historicise the ineffable—that which eludes words but manifests in gestures, objects, and images? For, as Xisco Mensua reflects, “no one can truly know what the night is like.” In this act of historiography, the artist, like a mourner herself, offers us an imaginary where representations stand as weapons of quiet tenderness, reminding us that Lanceta's work could not exist without the labour of others. Voices, resonating in textiles, words, and images, invite us to partake in this ritual of mourning. It is a new breath, but also an attempt—a step toward new affective ways of inhabiting time. As Sandra Santana writes, and as Lanceta illustrates, “we, the living,” united by a shared vulnerability, connected to them by an ancient inheritance that survives in our voices—for all those suffering today—we must let ‘our hearts devour the world’ before the shroud’s dawn awakens.