Publications

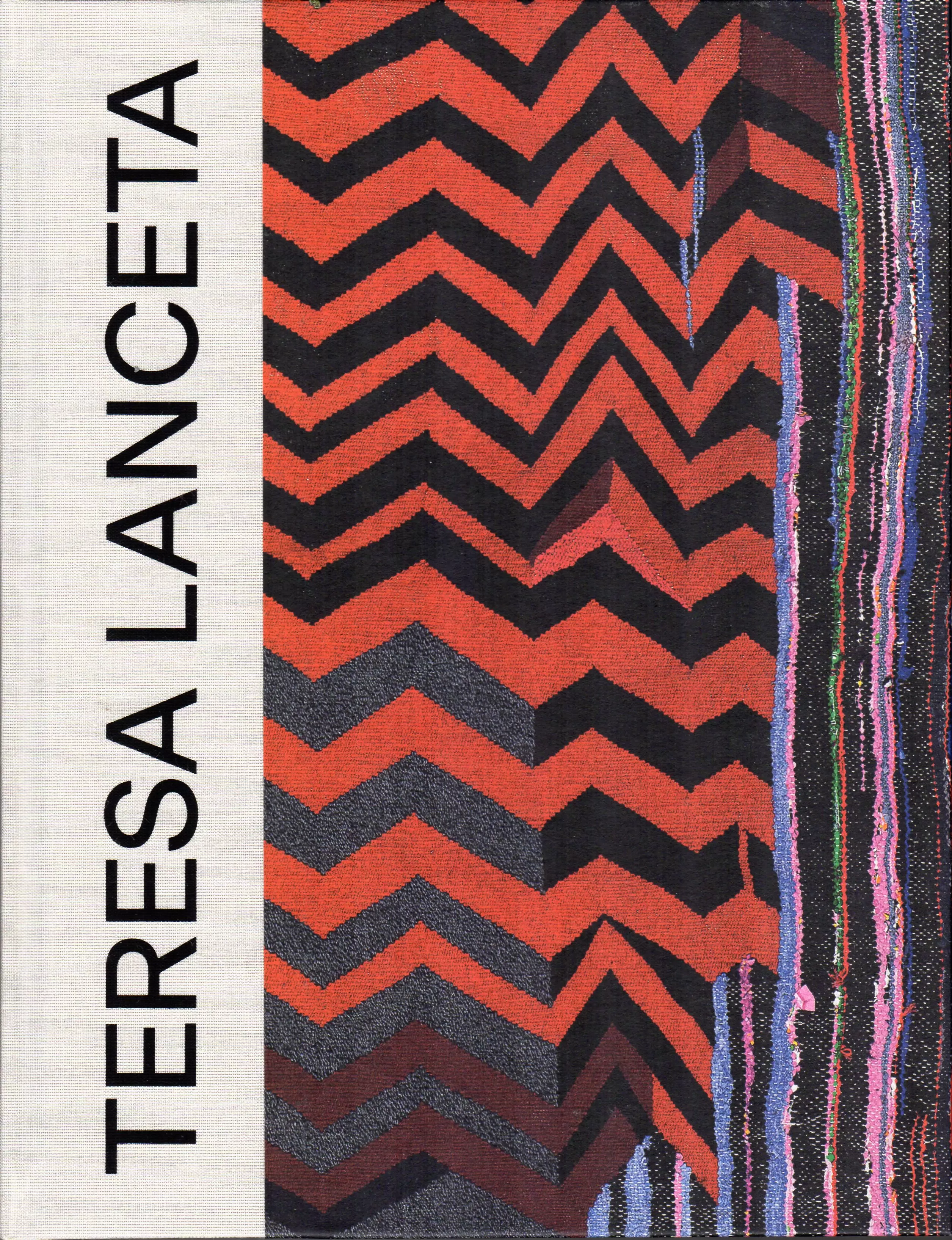

Teresa Lanceta. Weaving As Open Source

MACBA/IVAM. Curated by Nuria Enguita Mayo and Laura Vallés Vilches.2022-2023

Design: Hermanos Berenguer

Writings: Elvira Dyangani Ose, Nuria Enguita, Teresa Lanceta, Laura Vallés Vílchez, Miguel Morey, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Bert Flint, Pedro G. Romero, Olga Diego, Leire Vergara, Xabier Salaberria, IES Miquel Tarradell and Nicolas Malavé.

This catalogue, co-published by the Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona and the Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, is published on the occasion of the Teresa Lanceta exhibition. Teresa Lanceta. Weaving As Open Source, co-produced by MACBA (from April 8 to September 11, 2022) and IVAM (from October 6, 2022 to February 12, 2023).

Exhibition: Tejer como código abierto

Writings

- Waiting for the future - Nuria Enguita, Laura Vallés Vílchez & Teresa Lanceta

Conversation between Teresa Lanceta, Nuria Enguita and Laura Valles Vilchez

NE-LV From 1969 to 1985 you lived in Barcelona’s Raval district, then known as the Barrio Chino, specifically in Plaça Reial and on the Carrer Obradors and Carrer Jerusalem. In 1969 you enrolled at the Faculty of Philosophy and Educational Sciences at the University of Barcelona and began weaving. The Raval at that time was a mix of seaport, working class, migrant, gitano and Andalusian ambiances, and it permeates your entire work, nowhere so eloquently as in Life, and Now Too, Life, a collection of stories reproduced on p. 77 of this publication. Decades later, while living in Alicante, you went back there on a weekly basis, from 2013 to 2020, to teach at the Escola Massana, and returned again in 2021 for The Trades in the Raval (p. 305), a collaboration with Miquel Tarradell Secondary School, and to prepare your exhibition at the MACBA and the IVAM.

TL The Raval is a mosaic of diverse ways of living, cultures and even religions. Odours and features vary from street to street, and the neighbourhood has evolved with the times without losing its identity, which essentially has been and still is that of accommodating people from foreign parts, no questions asked. During the great exodus from the rural areas of Spain, many of those who came and settled in the Raval, or the Barrio Chino as it was known then, ended up working in the docks or nearby factories. Today, the incomers are from Pakistan, the Philippines... It’s one great human melting pot, with its day trippers and characteristic shops which, when I lived there, were largely devoted to sex. I can still recall the men in suits and ties who would come looking for women, transvestites and parties. No doubt at work they feigned disgust at this part of town! In Life, and Now Too, Life I chose the words to convey the memory of my experiences there very carefully – maybe that’s why it took me years to write it.

NE-LV You have sometimes said that the Raval has given you so much more than you have ever given back. But to us it’s obvious from reading your accounts ‘La Charo’ (p. 85), ‘Marina’ (p. 86) and ‘Rocío’ (p. 87) that through your relationships with these gitanas you shared a lot, a real mutual affection; you see this too in the stitched cloths and textiles that carry their names. In the ‘tiny home which had no bedrooms and no bathroom, and where curtains doubled as walls’, you say Rocío and her children endured ‘great hardship’. From the Patio Andaluz to the Tronío, through this exhibition we revisit some of these streets whose walls have now become fragmented or patched up pieces of cloth.

TL Of all the places I have lived in, the Raval is the least comparable to any other. Nowhere has given me so much, and nowhere have I felt so relaxed. The experiences the gitano community and I shared inspired reciprocated feelings, especially with those women, who saw in me a devoted paya (non-gypsy). In the early nineties, after living in Seville and then Marrakesh, I moved to Madrid, still carrying with me the memory of the Raval. I felt I wanted to talk about things that are broken, damaged, and mended. Waiting for the Future arose out of this feeling. It’s a series of drawings and stitched cloths painted over with pigments and scraped and rinsed to alter the textures. Then I mended or stitched over the damaged areas. The suffering poverty causes and the destruction it leaves are sometimes impossible to overcome. These cloths were painted and deliberately deteriorated again and again until the pigment was but a trace of colour. While making this series I felt a desire to make something direct and immediate that had nothing to do with the loom, which requires a lot of time to produce anything.

NE-LV You have indeed lived through many Ravals. The first you talked about just now was in the mid-seventies, when you moved there and lived with a gitano family. It was a conscious move, because you wanted to cut ties with academia and keep well clear of a regular job with a salary and a boss, etcetera. This idea of community and collaboration, would you say it has anything to do with the gitano way of life, their big families, how they look out for each other and are more used to moving around, leading a nomadic life? With living each day as it comes and ‘waiting for the future’, to borrow that phrase from a tango and the title of one of your series. In short, is there any connection with what Pastori Filigrana considers to be one of the reasons why gypsies are persecuted – they don’t adapt to the capitalist system of exploitation?1

TL This neighbourhood brought back memories of my father’s family. My father was from Seville, and his family was from Cadiz. The fiestas we had when I was a girl were generally very happy times. But I feel Catalan, and I think it is interesting to point out that what happened to me will happen to many others in twenty years’ time: they will feel Catalan or Valencian even though their parents came from a village in Morocco or Pakistan, and it will be plain to see. One of the pupils at Miquel Tarradell Secondary School (where Nicolas Malevé and I worked on a ‘co-authorship project’) told me that his father has two brothers in Britain, one in Canada and another in Italy. Will they ever be all together again? Diasporas have settled on both sides of the Ramblas: in the past they were from Andalusia, Extremadura and Galicia, and today they are from Pakistan, India and the Philippines. Nomads? Nowadays, you are a nomad by choice, and gitanos and gitanas certainly are. The others are displaced, banished. This is the neo-colonialism that’s happening in our streets.

NE-LV In 2019 and 2020 you produced a series of canvases, again on the theme of the Raval, but this time they replicate the colours of anarchism: red and black. It was the experiences of those years that informed them, mixed with issues we would like to pursue in the conversation weaving through the pages of this book: technique, memory and shared experience. Can you talk to us about these new canvases?

TL The more I worked on them, the more colours and shapes began to impose themselves. At first, there were blacks and browns or very dark blues with the odd dot of colour, but either because of lockdown or because of the type of black I was using, I felt increasingly drawn to reds. This is how I arrived at the red and black joined diagonally, which brought back memories as these colours carry a very specific ideological connotation; but colour and form brought me here. The CNT2-style diagonal correlates both colours without diminishing their chromatic intensity: it is sewn, stitched together. It’s not so much the tone that matters, but the saturation. Red fills everything when it spills over, and even more when it is contained. Red holds life and vies with black. It’s the opposite of black, not of white, as those who came up with the idea of pitching red against black for the CNT flag understood very well. They’re opposites, not because black denotes death (it does not), but because black is a lightless arcanum we feel compelled to penetrate. The same thing happens in the Raval. I remember the blackness of the corners I’d pass late at night as I went looking for strong colours like the ones we see in these canvases. Red was the blood that soaked his shirt because of jealousy and a knife. Black is the despair of nights spent sleeping rough. Red are the days of hunger. And red and black are the colours of lockdown.

1 Pastori Filigrana, ‘El ejemplo de los gitanos. Panfleto o discurso sobre cómo las resistencias al capitalismo del pueblo gitano están en el origen de su persecución’, Concreta, 14. Valencia: Editorial Concreta, 2019, pp. 40–53.

2 CNT. Confederación Nacional de Trabajadores, the Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labour unions.

- Vibrations - Miguel Morey

‘If one were only an Indian, instantly alert, and on a racing horse, leaning against the wind, kept on quivering jerkily over the quivering ground, until one shed one’s spurs, for there needed no spurs, threw away the reins, for there needed no reins, and hardly saw that the land before one was smoothly shorn heath when the horse’s neck and head would be already gone.’1

1

That writing and weaving are of the same family is clear from the word ‘text’, which comes from the Latin textus, participle of the verb texo, meaning to weave, plait, interlace. The gesture of writing, like that of weaving, consists of carrying the line to its end before continuing on to the next line. In writing, it is this feature that differentiates the movement of verse from that of prose, the latter having to go to the end of the line while verse breaks this continuity, often leaving a sentence in ‘midair’ only to conclude it in the following line, in what is known as enjambment. In weaving, too, the weft moves to the next line in pursuit of the pattern, the vertical. In Idea of Prose (1987), Giorgio Agamben locates the difference between prose and verse precisely in this particularity and establishes a connection with agricultural lexicon. Versura, in Latin, means the point at which the plough, reaching the end of the furrow, turns back.

I was reminded of this association between writing and weaving when I read Teresa’s texts about the Raval when it was still called the Barrio Chino. I realised that texts are woven too, for as we read them, we follow their ‘weft’...

Cervantes was aware of this too, as can be seen from the comparison he draws towards the end of Don Quixote (part two, chapter LXII) between literary translation and the back of a tapestry: ‘Still it seems to me that translation from one language into another, if it be not from the queens of languages, the Greek and the Latin, is like looking at Flemish tapestries on the wrong side; for though the figures are visible, they are full of threads that make them indistinct, and they do not show with the smoothness and the brightness of the right side.’

2

On the gesture of weaving, I remember something Teresa said to Marta González in 2000: ‘Weaving is a hypnotic technique, based on a repetitive movement, the results of which are not immediately apparent. The physical impossibility of seeing the whole piece as it is being woven, since it is rolled up as it progresses, enriches the fragment and gives it autonomy, while at the same time demands one has a global understanding of the composition that must be kept in mind for the time it takes to finish it. It’s a technique that encourages a peculiar and gratifying sort of concentration, although – as with any artistic activity, whatever the medium – nothing alleviates the strong tension and deep apprehension that accompany the creative process.’2

Furthermore, and especially, is the idea that weaving does not allow for any corrections of mistakes or any deviations from the initial compositional plan, which can be elevated to the category of a moral lesson one must not forget: ‘I see working a loom like life itself: what is done is done, and one has to live with it’.

3

Teresa and I first met as students while studying Filosofía y Letras (as it was called then) at the University of Barcelona (La Central). I began my studies in 1967, the year after the Caputxinada, when the Democratic Students’ Union of the University of Barcelona called the first elections. In the spring of my first year, we began to feel the impact of May ’68, after which nothing would ever be the same again. It was at about that time that we met. Chroniclers refer to those times (from 1969 to 1975) as ‘the years of student radicalism’. And so it was, and not just in Europe: in the United States, there were protest movements against the Vietnam War, hippy deserters, and the emergence of the underground culture – the counterculture. The Woodstock Festival took place in August 1969, as did the Harlem Cultural Festival (the subject of Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson’s recent film The Summer of Soul). At the University of Barcelona, 1969 began with a student assault on the rector’s office in an attempt to remove him. He was replaced by a bust of Franco but that ended up being sent flying through the air. On the same day as that event – 17 January – a student and member of FELIPE (the Popular Liberation Front) called Enrique Ruano was arrested in Madrid, but unlike the rector, he did die, three days later, at the hands of the police’s Political and Social Brigade. A state of emergency was declared throughout Spain soon after. From then on, university activities were regularly suspended, either on the decision of the academic authorities or by government order, because of the prevailing ‘situation of general ungovernability’, which is how our insurrectionary efforts were officially described. In December 1970, street protests (or ‘riots’ as the official reports called them) were sparked by the Burgos trials by military tribunal of sixteen ETA militants, resulting in nine death sentences being handed out (later commuted thanks to international pressure). Needless to say, this led to a new state of emergency being declared, first in the Basque Country and then throughout the rest of Spain. The following year, it started all over again: this time the trigger was the passing of the General Education Law, promoted by the then minister Villar Palasí (a member of Opus Dei). Fury raged for a long time. That was the way things were back then...

I don’t think we got through a full year of studies.

But I know that, as repression mounted, our desire for freedom was unleashed and somehow clandestinity became a way of life.

I also recall how in the early seventies heroin began to make an appearance at the University. ‘It was offered to anyone who was up for it, and practically all of us are at that age’, Teresa writes, adding: ‘The first time my generation looked out onto the world, they saw a poisoned chimera.’3 Take a walk on the wild side, sang Lou Reed in 1972.

4

For Teresa, the music that touched her heart was flamenco: el cante. ‘Flamenco thrilled me, and I learnt there that exception is the rule that makes us possible’, she writes.4 ‘El Tronío, El Camarote, La Macarena, El Patio Andaluz...’ These were all venues of fiesta y cante; of ‘parties, booze-ups, weddings and christenings...’5

‘When you get to know gitanos, live with them and delight in their art... when you discover their car pets, woven on mobile looms, the world becomes a bigger place. Your country is the ground on which you tread, and your home is always where you’re heading and not where you’re from because returning is not a going back but a perpetual moving forward. This is the rhombus. The rhombus isn’t made up of horizontals or verticals but of diagonals forming endless lines. In its reiterative expansion, the rhomboid lattice reveals no coordinates, no centre and no frame, but rather a network of equal parts. Repetition is not an enemy, but a value holding variations and transgressions. The rhombus is a horizon.’6

5

When things began to normalise in this country, following Franco’s death and the promulgation of the Constitution, Teresa and I lost touch and it wasn’t until many years later that we met again. Occasionally, though, and with increasing frequency, I would get news of her or her work. I thought I recognised in some of the things she said in interviews certain gestures, intimations of her personality I knew from our youth. Reading these interviews helped me to understand how to approach her work, to capture its ‘vibrations’ – to borrow a pet word from our student days. I actually think this word is quite fitting to talk about my experience of her work and to express what I feel vibrates in it and how; because whenever I look at a piece of hers the first thing I see, in rhythmic repetition, is that original moment of discovery of the cotton thread, the sudden fascination for the material:7 a love that found artistic expression in traditional handiwork, which shares this love of material and demands it be given adequate form. I see this same vibration when I realise that Teresa does not usually discuss how spellbound she is by tapestries (made in Morocco, for example) without also including the artistic ornamentation of everyday objects. Here, the vibration modulates: referring to the tapestry as a domestic object brings into view the house, and with it the working woman.8 Cue the Barrio Chino and its gitano vibe, where Teresa chose to live when she first started weaving. I remember the answer she gave when asked whether she was happy in those days: ‘Was I happy? I don’t remember now. Happiness wasn’t in my plans... although if I wasn’t happy, it wasn’t because of the biting cold or the sweltering heat or the cramped living quarters or the lack of money! And if I was, it would have had something to do with the flamenco way of life. To live and to be was what I wanted, to live like a gitana and to be – just that, nothing more.’9 Like a vibration in tune with something atavistic, powerful and elemental like cotton thread, which can still make its way through a multitude of labyrinths; a vibration that repeats itself, I think I see – infused by the constant presence of the working woman, by her dignity and her pain, her tragic knowledge of the way things are, her courage and her charm. And once again I recognise the vibration of when we were students that helped us to believe that reason had to come down on the side of the victims. And again when, in El paso del Ebro, she speaks of the girl who ‘wanted to know where her father was – like her fellow pupil who shared her desk, who knew that his father was buried in the ditch that forks on the way to the threshing floor’.10And again in the dedication of that text (a diary she kept of the weekly train journey she made between Alicante and Barcelona from September 2013 to July 2015): ‘To the Italian brigadista who, while awaiting his execution, carved wood... And to my great-aunt Teresina who would tell me these stories’. On 9 January 2014, the entry reads: ‘As the train passes Sagunto, I notice a CNT and IWA office and a red and black flag flapping around a short mast’. A happy sight, which is not repeated (7 February: ‘I couldn’t see the CNT flag on the premises’) until 20 February: ‘This time the CNT office is open, the red and black flag is on the right of the door and the windows are covered with posters’. She ends with a question: ‘How many members are there?’ And all too clearly, I understand – the reader understands – what prompted this question.

Looking at the series of five tapestries that are the premise of this text, I confess I cannot help seeing the railway as it crosses the Ebro River. I have tried, but it’s impossible. I imagine an old steam locomotive puffing out smoke, I hear the rattling and the clinking of the hammer as it knocks the wheels to check for damage whilst stopped at a station. I feel the powerful, swollen vibration of the river... A date comes to mind: 25 July 1938 – people say there was no moon that night.11

6

Between Franco’s death and the promulgation of the Constitution many things happened and with an intensity that has never since been repeated. I returned to Barcelona shortly before Franco’s demise and the following year joined the Faculty of Philosophy and Educational Sciences, as it was called then, as an assistant lecturer in its new location in Pedralbes. The city was humming with a tension that is characteristic of the creative process, as Teresa mentioned earlier. A profound sense of unease (the attempted coup d’état, known in Spain as the ‘23-F’, was only five years away) was offset by boundless joy: the joy of at last being able to breathe! The area where Teresa lived was now known under its new name, ‘the Raval’ and, without losing any of its distinctive vibrancy, began to feel a little like Manhattan’s Soho, which Pasqual Maragall would propose as a model in 1992. By way of an illustration, I will give just one example which I experienced at close quarters thanks to my friendship with Pepe Rubianes, who had been a class-mate of mine at university. In 1976, the Assemblea d’Actors i Directors de Teatre de Catalunya (AADTC) had designed a theatre festival, considered ground-breaking at the time, called the Teatre Grec, which has gone on to enjoy a very long and distinguished trajectory. A few months later, a splinter group of the AADTC formed the Assemblea de Treballadors de l’Espectacle and, for its first performance, put on several simultaneous performances of Don Juan Tenorio in the Born neighbourhood, which at the time was being claimed as the Ateneu Popular (a few weeks earlier the first libertarian Ateneu had just opened in Sants). And it was precisely this group – some 150 professionals at first – that took over the old Salón Diana cinema, with its 876 seats, on Carrer Sant Pau, and converted it into a place of first-class theatrical and civic experimentation. The Salón Diana opened its doors on Holy Saturday 1977 with The Living Theater (Seven Meditations on Political Sadomasochism), Les Troubadours and Dagoll Dagom (I Won’t Speak in Class) – and that was only as far as theatre was concerned, because the programme also included children’s matinees, late-night rock, zarzuela, dance, circus, cinema... You could just as easily find the clown Jango Edwards skidding across the stage on a powerful motorbike as a group of Yaqui Indians performing the ritual Peyote dance. The Salón Diana soon became a favourite meeting place, so much so that when La torna, for example, by Els Joglars (dedicated to Heinz Chez, the enigmatic Polish petty criminal who was executed on 2 March 1974, the same day as Puig Antich, in a manoeuvre by Franco’s regime to discredit him in public opinion) became a target in the notorious witch-hunt, it was turned into a permanent assembly. For a time, it seemed as if the city had found somewhere to exercise its right to assembly, not to mention all that was going on behind the scenes and in the bar La Piedra across the street. I don’t recall the moments Teresa and I shared in that adventure, or whether we came across each other at what turned out to be the culmination of all that turmoil: the International Libertarian Conference (Jornades Llibertàries del Parc Güell) the following summer. This conference was convened a few days after the CNT had managed to amass some hundred thousand people at the famous Montjuïc rally, from 22 to 25 July: three days and nights of non-stop meetings and debates, music and partying, with no one to answer to but the security guards deployed for the event.12 When I think back to those days, I can’t remember if Teresa and I met up then or not, but I have no doubt she was there.

I leaf through the pages of all the catalogues I have of her exhibitions, pausing here and there as if to double check something I already know and feel: that vibration I am beginning to recognise so well. Just as one can feel vicarious embarrassment, I feel vicarious pride when contemplating Teresa’s work, if only because of how she has sustained over time the gesture of honouring what one owes oneself just for being who one is. There is, furthermore, poetic justice in the fact that this work has been welcomed by the MACBA, that white ship ‘moored’ in the renovated Raval, with the skateboarders practising their moves alongside its flanks. It couldn’t be any other way, I tell myself, that we, friends from so very long ago, should be the first to be congratulated.

Miguel Morey

L’Escala, September 2021Miguel Morey is a philosopher. His last publication is Monólogos de la bella durmiente: Sobre María Zambrano (2021).

1 Franz Kafka: Wunsch, Indianer zu warden. Versuche über einen Satzvon Frank Kafka. Götingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2019. English version: ‘The Wish to be a Red Indian’ [trans. by Willa and Edwin Muir], in Complete Stories (Vintage Classics). New York: Penguin Random House, 1992.2‘ Si vivo, será mejor. Conversation between Marta González and Teresa Lanceta’ in Tejidos marroquíes. Teresa Lanceta. Madrid and Casablanca: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and Ville des Arts, 2000.3 Teresa Lanceta: ‘Early seventies: heroin and company’, on p. 79 of this publication.4 Teresa Lanceta: ‘Lugubrious’, on p. 78 of this publication.5 Teresa Lanceta: ‘La Charo’, on p. 85 of this publication6 ‘El rombo es un horizonte. Conversación entre Teresa Lanceta y Nuria Enguita Mayo’, in Teresa Lanceta. Adiós al rombo. Madrid: La Casa Encendida, 2016.7 Teresa describes it thus (in ‘El rombo es un horizonte’, op. cit.): ‘I lived in Barcelona in the seventies. All around me were these great conceptual proposals laced with political denunciation and I could see that what they were doing was really powerful, but something crossed my path, something I had never seen before: a skein of natural cotton thread (in those days acrylic was everywhere) and from there I went on to discover fabrics, especially the “popular” ones.’8 Ibid.: ‘Part of the artistic/feminist practice in the seventies was about critically and satirically decontextualising textiles. But I was more interested in discussing – in a positive way – the work of women that generated language and art through their own techniques and tools; women who, because of their doubly subservient condition – of being women and from poor rural areas – were ignored; women who defined and transmitted through their weaving the culture they belonged to; creators and masters of an artistic language that allowed them to explore the inherited canons and create objects that were undeniably art.’9 Teresa Lanceta: ‘Jerusalem, 8’, on p. 85 of this publication.10 Teresa Lanceta: El paso del Ebro (‘28th of April, 2014. Out- 11 bound’), 2016.11 Lanceta’s commemoration of the Battle of the Ebro, the project El paso del Ebro, which incorporates recycled objects belonging to the Centre d’Investigació de la Trinxera (Corbera d’Ebre), was presented as part of the group exhibition La réplica infiel (Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, Madrid, 2016).12 Barcelona Libertaria was a daily newspaper set up to cover all the events in detail. Downloadable on www.cedall.org (Documentació). - Life, and Now Too, Life - Teresa Lanceta

Life, and Now Too, Life

Because we live in homes…

A narrow street, a slender and steep staircase, a small building with negligible lightwells. An elongated flat with a constricted corridor where the light was always on; the third floor of a five-storey building. Seven tiny rooms, three of which were bedrooms holding not much more than a bed and a minute wardrobe each. One was occupied by Ch. and J.; the other by the grandfather (Ch.’s father) and the grandchildren; and the third by L. and me. Ours had to be entered sideways because the walls were covered in shelves stuffed full of our belongings, some of which also hung from the ceiling.

The communal areas: a small space with a balcony, where L. painted and the children played when he wasn’t there, so the painting utensils were always kept in our bedroom. This space, like the grandfather’s and the children’s bedroom, was adjacent to the living room and at the far end of the flat overlooking the street. Before reaching the other end, where the third – and windowless – bedroom was, you had to pass by a minuscule bathroom. Actually, there wasn’t anything you could wash in – no basin or shower – only a toilet with a high chain and newspaper which was used as toilet paper. To wash, you had to go to the kitchen and wait your turn!

In those days you went to the shops daily. Ch. would prepare gitano-style stews and cod and chips, but I didn’t eat them because I worked in a nearby restaurant. On Sundays we would buy several spit-roasted chickens and eat them straight out of the packaging. What a feast!

I would go straight from La Central university to the restaurant where I worked. My afternoons and evenings were free and we would wander about, tempted by the flagstones and the tarmac. We would move diagonally, expanding the narrow streets and squares. We lived in the streets.

One night, Ch. dropped a pan of chips on her belly. We went to A&E, where she was given an ointment, antibiotics and painkillers. Back to work she went, all wrapped in bandages. There was no way she would miss work and forgo pay. She also feared being replaced.

Now that I have become obsessed with the idea of changing where I live, I think back to those meagre needs we had then which, perhaps because they were so meagre, were easily satisfied. We had very few belongings and our furniture was minimal: just a chair each, two tables, beds... We had no sofa, no armchair, no ornaments; only a television for V., who would thump it each time the picture acted up. The flat was old and hadn’t been touched since it was built more than a century ago. The floor tiles, wall tiles, woodwork and lights were all original. There were no decorations or photos on the walls. The few photographs Ch. and her family had were kept in a box with other papers, and I have always been loath to keep personal photographs.

The walls were green in the dining area: the lower section was a hard- wearing gloss paint, and the upper part tempera. I have no memory of that house that is not tinted green.

The grandfather had interlaced the deep sadness caused by the death of his wife with the ‘loss’ of his only daughter, Ch., then a young and beautiful fifteen-year-old, at the hands of the elder gitano whom he had entrusted with her protection during their tours along the Costa Brava, a charge he failed to honour when one night on a train the old guitarist and the young dancer were up and on the lookout for love. The two men never spoke a word to each other again, and the guitarist, who was now father to his three grandchildren, shared a bed with his daughter while keeping up visits to his other family too. Home is where happiness comes to settle, although not always.

Lugubrious

How a lugubrious place can appeal to so many, and how I felt so at home in one.

In the early seventies, home for me was the Barrio Chino in Barcelona – and not just the four walls around my bed, bathroom and kitchen. The streets and everything they entailed were my home. We would bundle down the zigzagging alleyways on our way through life – some of us more surefooted than others – meeting up with friends, gitanos and gitanas along the way, many of whom – the women – became my friends too. We didn’t just run into each other; we tracked each other down, hunted each other out: they looked for and found in me what I looked for and found in them. My surroundings ended up being part of me.That shoddy district, home to the down-and-outs, the wretched, the ailing, the ragged and the humiliated, was a haven of joy and fantasy washed down with copious amounts of manzanilla sherry, gin and tonic and White Label. The beer came later... to which some people would add other substances too.

Completing the picture were the day-trippers and punters. Some came because here they felt good, they felt respected, unlike in their work-places or everyday lives where, if they showed their true colours, they were singled out. Others came looking for darker ambiences or fluorescent sensations they could dilute in hopeless joy. Certain very powerful people came too, attracted by the bitter smells, the merriment and the pain inflicted on streets strewn with rubbish and bags of dubious contents.

In the Barrio Chino, known today as the Raval and Gòtic Sud, neon lights lit up the nights. I would have been no more than twenty years old when I first arrived. My younger self surprises me: shy as I was, I would perch myself on a stool in a flamenco bar or in a tablao and defend my square foot of space, feeling present yet absent, and listen to Charo sing and dance or to Juan or El Gato play the guitar... I ‘found myself’ in the glory of El Tronío, El Camarote, La Macarena, El Patio Andaluz, in these places of fiesta y cante.

I didn’t find there anything I already knew; I didn’t discover that dark mystery glimpsed in childhood or adolescence – I just felt good. Flamenco thrilled me, and I learnt there that exception is the rule that makes us possible.

It’s not that I didn’t see what was going on around me or that I wasn’t conflicted by it at times. I did have clashes and run-ins, particularly with a pimp who was a gitano, a relative or close friend of Juan’s, who often used to come with us to parties, christenings and bars. We were wired very differently and although for obvious reasons we tried to Cripples keep out of each other’s way, it wasn’t always possible. Sometimes we would end up shouting and hurling insults at each other, but there was always someone who would step in and try to calm things down. His women avoided me and I them, so I don’t remember much about them, except that they worked a lot and he made them work even harder.

Cripples

‘It always surprised me that when we were sitting there on the terrace of some bar, we did not feel our hearts break at the sight of so many invalids, many of whom were operable. No, Jemaa el-Fna, the square to beat all squares, absorbs you into its circle and you end up seeing only an expanse of people whose struggles extol life. The pain never goes away, it is anaesthetised.’

Night came before sleep. Fallen light is very beautiful.

There were lots of cripples back then. The definition of the term ‘cripple’ given in the dictionary describes most of them well: ‘as having lost movement of the body or of any one of its parts’. I am not talking about the handicapped or the disabled looked after by ONCE, Caritas or church parishes, no: these were Barrio Chino cripples, with very visible and clunky iron contraptions propping up their legs. The pain these things caused them must surely have taken some getting used to! There were others, too, with poorly simulated artificial hands or arms.They all moved in Frankenstein fashion. It wasn’t as bad as what I saw in Morocco years later, but not far off. Others moved about in manual wheelchairs. These invalids distinguished themselves from cripples by their need for a companion, a kind of walking guide that would often double as an extra mischief-making hand.

In the Barrio Chino nobody hid their misfortunes; maybe because, although natural or inflicted cruelty happened all the time, luck dealt a very mixed hand when it came to how the blows were suffered, even amongst those who were blessed.

Lifestyles were pursued in a variety of ways, but all had one thing in common: the need to survive – and by whatever means possible. This meant running errands and favours against a backdrop of precariousness that bordered on skulduggery. Survivors’ ideology. The blind ruled, for they saw without the use of their eyes.

Extreme privation was particularly evident in relation to the police, who were distrusted and secretly despised. But they were also admired, and people would cooperate readily enough, especially if the officer made himself part of the fabric of the Barrio Chino. Embodying authority and power, he was both feared and accepted.

In pursuit of oblivion, the cripples and the alcoholics (later outnum-bered by drug addicts) would congregate around bar counters in daily communion. Sustained by the idea of possibility, some came in seeking refuge from their daily struggles while others seemed to have been blown in by the wind.

Floating was an art, and it’s how the barrio kept itself going. The gitano ambiance drew in the crowds: art and violence as survival... So here was one selling lottery tickets ‘con arte’, another there singing ‘con arte’, another swindling with guile and another using con tricks to get brass.

Amid such masters of chicanery was the occasional murderer, like the newly wed policeman, who shot his pregnant wife with his firearm. He wasn’t a cripple though: he was young and strong and in receipt of a monthly paycheque.

(Teresa Lanceta: ’Lived Cities’, Luis Claramunt. El viatge vertical. Barcelona: MACBA, 2012, p. 265.)

Early seventies: heroin and company

It was at university and not in my neighbourhood where I first came into contact with heroin. But had I been working in a warehouse, a factory or an office instead, I would have encountered it there too, because its happy aura meant it infiltrated everywhere. In it came, stealthily; and by the time we realised, it was already in our streets and in our lives. We didn’t see it for what it was because in those dictatorship years we were rough, untravelled, frightened and inexperienced; and the glamour around the drug offered us a glimpse of cosmopolitan life, nirvana and elegance.

It was at university where I was given it, along with a fair amount of sweet-talking. It was offered to anyone who was up for it, and practically all of us are at that age. Fellow students from well-to-do families would bring it back from long exotic trips to Afghanistan or India, dressed in robes embellished with tiny mirrors and coats, like the one Janis Joplin wore in that famous photo. They brought that thing that was only ever talked about in hushed tones. It was the title of a song we listened to but didn’t understand.

These ‘dealer’ classmates were apprentices in the clutches of adventurers who were not averse to lining their pockets. On the contrary, they hoped to become rich, surround themselves with beautiful women and surpass the lacklustre bourgeoisie of their parents. Crafting false and harmful illusions is the same sort of tactics that wolves use to overcome lambs. And we were all lambs, including many of those novice dealers who went from fantasising about mafia power to experiencing first-hand the horror described in the Midnight Express and so many other films on the subject.

In my case, I was approached by classmates accompanied by a very young couple, like us, but much more worldly. They wore expensive Italian designer brands that we had never heard of while we went about in our cheap nondescript clothes. Boasting about trips to Italy and transits through airports we hadn’t a clue about, with their refined manners they would express how keen they were to have a tapestry of mine or a painting by Luis. I remember we got all excited about it; and then it dawned on us that they had no intention of giving us in anything in exchange but a few grams of powder. I didn’t really understand this until much later, but I remember being rather peeved. And I wasn’t much impressed by one of the substances they gave us, although it was good to be able to fling open the underground doors which were normally a little stiff!

It all ended badly, very badly, for my classmates: Take the bag. No, you. You. Noxious suspicions and eleventh-hour forebodings in an Italian customs office and before long they were taken away and locked up for many years. And as for that ‘high-class’ couple that had circled us like birds of prey, a mixture of violent recriminations and measured caution put paid to them.

A friend of mine was related to a certain piano-playing minister who years later was caught at the centre of a corruption scandal. It doesn’t look like this connection was of much use to him because he got put in the clink for years and after his release he died, either out of choice or out of despair. He wasn’t the only one in my circle to have gone down the same disastrous path or the only one to have paid for it with their life. Trips that end in tragedy. The first time my generation looked out onto the world, they saw a poisoned chimera.

Meanwhile, in the streets more than in the university, the ravages spread, and the young gitanos in my neighbourhood got sucked in. But that’s a story for another day.

U

For some, the letter U represents a dead end, but for me it was the shape of the route I took of an evening: a line, a couple of ninety-degree turns, again a line. Two parallel lines. U for the ubiquity of conflicting desires.

After dinner and sometimes after studying a little, I would set off on the U that began at my doorway and ended where Charo worked. I would start at Obradors, turn onto Carrer d’en Rull, then again onto Carrer Nou de Sant Francesc, and continue until I got to El Patio Andaluz, which is now a warehouse. Opposite is an alternative rock venue but back then it was the tablao La Macarena.

And such is the path of life: a U. There’s a beginning, a journey and an end, like the one I traced, following the course of my own thoughts from my front door to the flamenco ‘pick-up joint’ – although what people came to find wasn’t so much female company as singing, guitars and dancing, because El Patio Andaluz was not exactly a tablao (although there was a small stage for performances), but a place where the artists would mingle with the clientele and get them to drink as much as possible to prolong the performances. Afterwards, clients would be charged according to how the night had gone. This intimate and direct way of doing things was an early flamenco tradition, but by the 1970s it had been replaced by the tablao show.

Like the U, a beginning: sharing a flat and my life with a gitano family. And an end: Juan’s murder. A beginning: flamenco understood as live art; and an end: that of a world and a way of making a living.

The route through those three narrow streets was more than a mere act of passing through: it was the channel that directed my longing to listen to a cante and see people I loved.

Pressing desires

When the night ends, desires become pressing, desperate. The dawning day burns them and then disenchants them.

They were having a last drink at one of those little market counters that opened at sunrise. Daylight revealed the ferocity of the desire for the transvestite. At that hour, there was no concealing it – the craving was urgent and it maddened them: they didn’t want to prolong the fierceness of the moment any further. Men in suits, apparently quite collected, would start to unravel at dawn – the hour at which their families would give up hope as work beckoned.

The Rambles, Barri Gòtic and Plaça Catalunya make the Raval possible, just as the Barrio Chino once had. They serve as glamorous boundaries containing the poverty, dirt and desolation, and allow the outsider to dip in and out. Tourists feel comfortable in these places because they know they won’t be staying forever; but for the residents these boundaries are barriers they are unlikely to cross. In the Barrio Chino, youngsters would drop like flies, and children showed early signs of following in their footsteps. Many came from La Mina or El Camp de la Bota. Today they come from the East, both near and far.

The street belongs to those who claim it – sometimes – because nothing generates greater submission than power. It’s understandable. There aren’t enough trees. But what can you expect from a neighbourhood of hidden desires?

I do not remember his name and I will not say where he came from. He had been ‘banished’ by his father, a high-ranking military officer who had sent him to Barcelona after the secondary school where he had taught expelled him for inappropriate and abusive behaviour, he told me one night, as the two of us sat on a bench in Plaça Reial. He was there to keep a low profile.

On his TV, but in my flat, every week (I think it was on Mondays) we would watch Rito y geografía del cante flamenco, which brought us closer together than the fact of living next door to each other. He wasn’t particularly interested in flamenco, but for him this was a moment of relaxed neighbourly relations.

How would he have been judged today? It’s hard to say. I don’t know if what happened was prompted by a shared desire that was punished in those days or an abusive situation. He was weird, really weird: his flat was carpeted in fine black lingerie. When walking on that soft, slippery floor of bras, garters, corsets and panties became impractical, he had a mezzanine floor built to hold his bed, which also filled up quite quickly. I left without knowing where fate would take him and his lingerie collection. That flat next to mine has been home for many years now to a well-known comic artist whose work I like very much.

You grab your freedom with a degree of guile, at least when civil rights are scarce and your determination is strong. Others adopt a low profile and go unnoticed, although at any moment one risks being torn to pieces by someone in a better position. Ocaña, Nazario and some of their friends saw it for themselves when they were sent to prison in application of the Law of Vagrants and Thugs which locked up gays and ‘weirdos’.

Oblique streets

Oblique were the streets, glances and youth that squandered their vital energy and wore themselves out before their time. Oblique were the sentiments, magnified by the pressing need to make a living, prolonging the precariousness of the post-war period. Children grew up amidst these adult vicissitudes, getting ahead however they could, barely aware of the meagre sun that filtered obliquely through the balconies.

In this coded world, one practised the art of seeing without looking, or without appearing to pay attention; furtively, as the Pakistanis still do. Given the extreme closeness of our streets and lives, it was better to get wind of things and avoid unwanted revelations and intentions; in other words, it was better to keep out of the way of gossips. It was a world in which a sideways glance was enough to allow you to size up the other side or give a wide berth to snobs and bores; but it was also a world in which you didn’t take your eyes off the fictitious horizon.

The streets of the old Barrio Chino would be teeming with people on the go, people lying low, and curious individuals slipping into bars or leaning against a wall in guarded anticipation. You recognised people by their side profile or by the gesture they made as they lifted the glass from the counter to their lips. Over time, these profiles have softened: nowadays, you rarely see aquiline noses or marked cheekbones – signs of dire need, old age or missing molars. There were many bad men among them, but their kind of evil was driven more by necessity than nature. Even in that respect they were poor.

An empty gaze; seeing without looking, looking into the distance... oblique like the death that befell Juan, with a direct and well-aimed stab. An evasive look, a squint, a sideways look. What distrust!

Crooked hearts... always so hopeless, what has become of you?

The slanting streets of Escudellers, La Riera Baixa, La Cera and so many others... Their finest hour: the oblique night.

I was never afraid of those streets, the seedy joints, the people; but that was then: now I am overcome by fear.

31 August 2016: the Investiture

Leaving the Barrio Chino was quite an event for its residents, and still is today. Having made it my stomping ground and considering anything beyond its boundaries almost a foreign land, my daily foray to La Central university, where student life carried on as normal, was something of an intrepid exception. All the way from Obradors to Plaça Universitat, all I saw was how wide the streets were and how much sky there was above the buildings, and my short walk was transformed into a dreamlike voyage.

Whilst at university, every week I would go to the Llum de la Selva, one of the first places to do Gandhian-vegan-raw food anarchism in Spain, and at night I would go out partying – but I kept the two worlds separate and neither knew of the other. I practised a sort of intimate compartmentalisation built on omissions, even lies. It was a fairly common thing to do then and meant keeping things under your hat or keeping a low profile. A split personality helped you navigate your way around situations which, if you had to confront them face on, would require a renunciation of some kind. Sometimes, choosing means sacrificing something you love. So, with as much audacity as spontaneity, we would juggle discord to avoid upsetting the whole structure of our lives. Already as children we learn to pretend and keep up a deceit for as long as it takes to avoid being found out... or to escape punishment.

Living like this is complicated, contradictory, and sometimes painful, but it helps to reconcile desires with puritanical impositions, unfair persecutions and truly incompatible situations. It is not reprehensible, not strictly speaking, for it is part of our makeup, our freedom and our right to it. Squaring certain experiences would be impossible otherwise. It is a ploy we use in situations we find hard to cope with, if also and ultimately but a vain attempt to escape misfortune or a tight corner.

On the flip side, though, hiding behind the same veil are malicious and unscrupulous people who do immense harm to individuals and society. Instances of this abound, ranging from the banal (adultery, kleptomania) to serious cases of corruption, fraud and undiscovered crimes. I don’t include spies or clandestine resistance fighters because, although their tactics are similar, their motivations are different.

The Barrio Chino is well versed in split identities. Founded on the frustrated desires and secret yearnings of its inhabitants and sustained by prostitution, alcohol and drugs, it is torn apart by exploitation, iniquity and injustice, and any glimmer of joy is buried therein.

Now, as I listen to the radio covering the most depressing investiture I can recall, I reflect on this intimate dismemberment that began when I was a child, and a dismal dreary emptiness fills the space.

Patrons of the night

Patrons of the night, the movers and shakers of surplus... those for whom no expense was too great. With them we would wind up the night, in the beach bars of Barceloneta, just before dawn, like vampires, before the light of day hurt our eyes and our dreams.

Awaiting us were early morning paellas, comforting mussels and prawns that come in a sauce that stains the serviettes red, plus the odd more distinguished shellfish... With these offerings the night held out and desire grew. The owners would sit with us, and through banter and laughter we masked our tiredness and warded off the daylight and with it, the sadness, the melancholy. I was young and shy, so I never asked for – or was given – anything fancy lest the bill went up but not the portions! There were no cash machines or bank cards back then, so wads of banknotes were counted by hand: whatever was in the old man’s pocket had to reach the flamenco artists whole. We never bathed in the sea, and we kept the sun at an angle for it pierced our senses.

Between the patrons of the night and the artists was a long-standing bond based on generosity and acceptance; a certain give and take, a mutual respect. The trust and friendship were real, even if they were arbitrated by economic transaction. Earning a living entailed drinking, living the art with abandon, and overseeing and sharing out the money among all the guitarists, palmeros, cantaores and bailaoras. The more the needs, the smaller the shares. Making a living requires caution and restraint. And alcohol should not be allowed to distort either the situation or the distance.

We would occasionally be invited to parties in uptown Barcelona, where we’d find ourselves in empty white spaces surrounded by lots of money and glamour. White kitchen, white bathroom, white walls and white furniture... The flamencos didn’t appreciate this at all, much preferring the dark green and blue walls of our red-floored homes and our rickety fake wood furniture rescued from street corners. How many maids did they need to keep those surfaces as white as the powder that filled their lungs? The colour of absence... which you could see in the scant attention they paid us. Flamenco nights spent in passing.

I try to imagine dawn in Barceloneta today after a night of fiesta flamenca, and suddenly I hear Rocío’s laughter.

The neighbours

On the corner of Plaça Reial and Carrer del Vidre stood a huge, dilapidated building, the third floor of which had been divided into lots of small rooms. All of the following at some point lived there and had been neighbours of ours:

Adulterers. In the seventies divorce didn’t exist, so one solution around illicit encounters and marital disharmony was adultery, which is what we believed a well dressed middle-aged couple were doing when they dropped by of an evening, keeping a very low profile. We never saw them up close and only caught glimpses of them when the door opened or closed, which also revealed an oriental rug and a sofa that contrasted boldly with our paltry belongings, and only fed our fantasies, poor curious neighbours that we were... We did, after all, share a wall, a staircase and a main door.

The Diogenes of lingerie. As I have already said in another story, this man was really weird, though very discreet. For us, peculiarities were something normal – not only his but those of others too. He wasn’t a queer that had to be accommodated; he was simply a neighbour, like the spirited and effusive Ocaña.

The one who was always shouting and arguing. He had occasional lovers with whom he would quarrel. He was a pilot or worked at the airport or something like that. I tried not to have anything to do with him and kept out of his way.

Mariona and Toni. Mariona fled to some Nordic country (Sweden?) to escape prison when the political-social police got wind of her. When she came back she set up the puppet company Malic. I was very fond of her: she was warm and affectionate and helped me understand life and art. Her words gave me strength. She was deeply feminist, although we didn’t speak in such terms, and the antithesis of the pally artistic banter of our partners. The way she understood time and things generally contrasted sharply with the anxiety felt by the male artists. She died young, in 2007, and I miss her.

Ocaña. I remember him exactly as he went down in history: funny, clever, brave, always inventing and creating things. His life was one continu- ous ‘performance’. We didn’t remain in contact for long.

Nazario lives there now. He is the only one that remains from that era. I’m glad he is still there because no one else has managed to stand up to the onslaught of tourist flats: one by one, everyone has left. Nazario has joined together two rooms: the adulterers’ one and the one L. and I had. He has made the most of the high ceilings and has had a loft-bedroom put in. It is very nice, especially because of the views it has of the Vidre alleyway and Plaça Reial. A large ‘room with a view’, kitchen, and a bathroom, which is now inside the flat and not in the communal corridor as it was when we were there.

One day I went to say hello. It was nice to see the place again. I didn’t feel nostalgic so much as honoured to have lived in this magical place that is Plaça Reial.

El Tronío

Engulfed in the darkness on a deteriorated road, like the Barrio Chino.

El Tronío was a tavern run by an old lesbian couple who spoke and acted like gitanas straight out of a time and a place where el tronío (a certain flamboyance of style) was the thing, hence its name. Well-groomed and poised, they were more Pastora Imperio than Lola Flores – more enigmatic than frisky – and they kept their customers at a haughty distance, barely even looking at them at all.

The place had a high wide bar of gleaming white marble and a few tables. Flamenco played, and on certain occasions there was also singing and dancing. It looked more like a pick-up joint than a tablao – and perhaps it had been that. The clientele was a bit decrepit, flamenco (of course) and of generally modest means. The lavatory doors didn’t close properly and there was no toilet paper, at most a scrap of newspaper, as was the norm in the bars of the Barrio Chino that weren’t frequented by outsiders.

I liked it there.

Jerusalem, 8

Barcelona, 2017

It is amazing to think that some thirty-five square metres could hold two studios: L.’s, which also contained our bed and a cupboard, and mine, which had my loom (1.60 m wide) and a guest bed; plus a corridor-storage space, a toilet, the kitchen and a dining room with a drawing table. All this under a roof patched up with uralite and tiles! Home for us was a dovecote on a thirty-degree sloping rooftop terrace for about eight years, which is quite a long time compared to the other places I’ve lived in. Light and sky... That’s what it was.

Was I happy? I don’t remember now. Happiness wasn’t in my plans... although if I wasn’t happy, it wasn’t because of the biting cold or the sweltering heat or the cramped living quarters or the lack of money! And if I was, it would have had something to do with the flamenco way of life. To live and to be was what I wanted, to live like a gitana and to be – just that, nothing more.

La Charo

Knowing Charo, to think that the ‘Dr Mabuse’ Nazis chose Romani people for their experiments on account of their physical strength and tremendous resilience sends a shudder down my spine. For Charo is the perfect example of these qualities, capable as she was of adapting to and surviving the most terrible adversities. She belongs to that caste of female survivors who have seen all their men die in dramatic circumstances and yet remain unbroken and powerful perpetuators of the species.

She was big, beautiful, dark, very gitana and very loud. She was related to Carmen Amaya. She sang well and danced amazingly. She earned her living in a tablao. As she was paid by the day and had to support her family, she never missed work, not even for reasons that any other mortal would consider grounds for sick leave or force majeure. In this she demonstrated her strength. During the time we lived together she had several abortions but never considered this justification for losing a day’s earnings.

It took me more than three months to make her understand that the Pill had to be taken daily, as part of a cycle, and that the reason why she was constantly getting pregnant and having abortions was not because she was fertile and other women were not, but that her method was faulty because she only took the Pill when she slept with her husband. Correct information didn’t improve things much because she was so temperamental and so clueless that there was no convincing her to keep taking it, even if that meant arguing with her husband, just in case... and her ‘just in cases’ were indeed exalted affairs.

To say she lived each day as it came isn’t quite correct. She lived each moment, and my memory of that time is full of fluorescent colours. He was a tocaor and she was a bailaora, so life for this couple was a string of parties, booze-ups, weddings and christenings. I was only twenty years old when I started living with them, and seeing them so cheerful, I could not have imagined the tragedies and dramas that continually befell them. But it wasn’t long before I learnt of the terrible fatality that tyrannised their existence.

Charo went through a terrible time when, in the space of a month, she lost her father and husband in unfortunate circumstances. She then fell into the arms of an evil man who treated her terribly. The tablao where she was employed went out of business and she was forced to take up work in a brothel.

Her long years of suffering came to an end when a young and handsome Galician man with a thriving business entered her life. He gave her children employment, thereby taking them off the streets, which were already beginning to fill up with heroin.

I went to Barcelona a few years ago and paid her a visit. She told me that the ‘Galician’ loves them very much, her and her children, and that he is crazy about the daughter they have had. She tells me that the ‘Galician’s’ family is a good to her. And on she goes, without ever mentioning the ‘Galician’s’ actual name. As I look at her speak, I remember how her father and husband used to abuse her, and I can’t help thinking how little suffering and adversities matter when it is passion and blood that drag us into them.

Marina

An ocean, many miles of land, sea and air separate us, but I swore to her that I would accompany her to the doctor.

Marina is still beautiful, but she’s bloated and anxious. She goes from one doctor to another, swallowing pill after pill, most of them incompatible with one another, and in crazy doses. She doesn’t understand the instructions and gets overcome by ignorance and despair.

She is a Giotto virgin, big, motherly, a refuge. As a child she was an expert at climbing trees and hunting birds. Now she has six men in her care: a husband, four sons and an unmarried brother. She washes, irons and takes care of them all. When she serves the stew at mealtime – her husband first, always – she appears transfigured, she glows. Active and cheerful, she laughs constantly, but to me she seemed bitter and tired.

She loved her husband and when they married it was for love. The problem was that masculine anxiety that made her husband jealous when he saw she was happy, and he would fly into a rage and hit her.

Now, we are a long way away from each other, but I still remember those walks we used to take together, talking and laughing – her always with a child in her arms, and me happy to be by her side. I remember so many weddings and christenings where we danced and sang. And I realise that all that is now in the past, because the last time I saw her in that pristine village where she lives, we had both lost some of our old sparkle. I looked at her and saw how she had been affected by all that gratuitous violence which she accepted with an ancestral resignation while her heart had eroded, as mine has too for having witnessed this, for having loved and respected her husband and shared with him the stew she prepared, though it pains me now.

Maybe this is why I remember my promise to her that I would come back and accompany her to the doctor, and I have not kept it.

Rocío

Rocío wasn’t hired by venues or tablaos. She was only ever called when someone needed a full private flamenco setup. Charo would call her because her style of singing was great for dancing, she was cheerful and good at rousing the crowd. She scraped a living by singing, which she supplemented with poorly paid jobs she kept under cover. In her tiny home which had no bedrooms and no bathroom, and where curtains doubled as walls, she and her children suffered great hardship.

This blond gitana from Granada had several children by men who were either long-gone or dead, but all had been abusive. The evil had rubbed off on one or other of her offspring and ruined her life, destroying her ability to keep the family together.

Rocío did not sing the cante of Jerez or Utrera with its deep tragic ayes, but I am still moved when I recall her deep sense of rhythm and the expressive intonation with which she sang: ‘Tú vienes vendiendo flores, tú vienes vendiendo flores, las tuyas son amarillas, las mías de mil colores’ (You come selling flowers, you come selling flowers, yours are yellow, mine are a thousand colours).

Recently I heard her sing on a corner of Carrer Escudellers: there she was, my friend, sitting on a low wicker chair, but she wasn’t singing tangos. She was chanting out lottery numbers!

Juan

Juan was known as El Perro. By his own account, he was given the nickname as a child by some gitano neighbours who saw him eating bones. It was used by friend and foe alike as it was a good representation of what each saw in him. For a few years I shared a home, my life and friendship with Juan and one of his families.

Like many gitanos, Juan looked rather like a Native American warrior from Arizona: strong, on constant alert, tense, distant and stiff, his skin more coppery than dark, his hair long and shiny and slicked back. He played guitar at tablaos and fiestas. His playing style was terse, no frills. He could be found at El Patio Andaluz, El Camarote or El Tronío, in the streets off Escudellers, right in the heart of Barcelona’s Barrio Chino. These places weren’t popular with tourists or especially varied in clientele; only devotees – Catalan or not – of the purest flamenco came to these venues.

Juan was a solitary figure and well respected. The first time I saw him he was sitting outside a bar in Plaça Reial. It was summer and he was wearing a very tight, see-through red lace shirt. He was in his forties and he had two families. It was with his second wife, Charo, her father, Valentín, and their three children that we went to live. A distant cousin of Carmen Amaya, Charo, was as young as we were. She danced and sang with great intensity and I went along with her to many parties. Juan never defaulted on either of his two homes: with Charo he would have dinner, they would go to work and come back together, and he would leave her at dawn. He would go to a poblado on the outskirts where his other family lived and return to the Barrio Chino again at night. All this caused him a great many complications and much ducking and diving. With no salary and no security, he depended entirely on customers to make a living, so off he would go with his guitar, seeking a living from venue to venue in one long non-stop party.

But joy in the Barrio Chino is fickle, and fortune wreaks havoc with people’s destinies. Juan died an absurd and tragic death: he was stabbed in the heart. Caught in a scuffle, he was held back by friends in an attempt to appease him, but this only cleared the way for the knife to go straight in. His death was deeply mourned because he was loved. The assailant served a two-year prison sentence, claiming in his defence that Juan had a pistol in his guitar case, even though he knew – as we all did – that it was a toy gun and hadn’t been taken out of the case that night. No-one at the trial contradicted the version of the aggressor, a gitano too, who had a previous conviction for something similar.

The cante gitano, with its heart-rending beauty, eases the cruelty of life and the pain it brings. Luis must have understood this when years later he painted a portrait of Juan with his guitar.

El Gato made a living through singing and, in summer, he would tour the Costa Brava as part of a flamenco group accompanying Singla, a barefoot bailaora. He was also the driver of the van that took them from one place to another. As soon as these summer gigs were over, he would return to his base in the Barrio Chino and go out every night in search of new earnings. He had many children. We named one of them: he was one of us. When hardship hit, El Gato went to France, like many gitano families, lured by a law designed to raise the birth rate through financial incentives.

(Teresa Lanceta: ’Lived Cities’, Luis Claramunt. El viatge vertical. Barcelona: MACBA, 2012, p. 235.)

The seducer

It was an era of cheap wine and insatiable hunger. Food was costly and junkies had mothers and families to keep.

When J. died, passions were ignited, and everyone, young and old, married and single, tried their luck with the young widow, who complained of the ignominy of the situation: that she, a gitana, should be harassed by other gitanos whose wives she knew. She was especially narked by the attentions of those who were last on the list of possible candidates – for she too had felt the stirrings of desire, and why not? Now that J. and her father were dead, she was free and wanted to choose for herself.

She’d had three children in eight years with a man her father’s age, a man who had had two families: the one they had created together and the one he’d had before and never abandoned. And he had had lovers, as everybody knew. And for the love of one he had been killed.

She chose Joselito. I wasn’t surprised: they worked together, and he was especially tender and seductive with her. He loved her, he really did, but the fragility of his wife – a first cousin – and children, two of whom were disabled, prevented them from ever living together. Still, tending to their passion must have been fun. They loved each other.

Valentín

Some people wallow in the gloom of their unlucky star and only rarely step outside it, perhaps during the fleeting years of their halcyon youth, when the splendour blinds them to the ugliness and meanness and despondency that later on snuff out any glimmer of hope. So it was for Valentín. With his black hair, spit curls and chain-smoking, he camouflaged the alcoholism that a life of vexation had led him to.

As his wife sold flowers and his only daughter had quickly flown the nest, Valentín didn’t have to work too hard. As a young man, when he had felt strong enough, he’d worked down at the port unloading sacks. In those days, men were picked from a crowd of hopefuls that would form daily in search of work (as is happening again now in village squares during the fruit picking seasons; and on our doorstep, in Atocha, where cheap labour is sought for work on illegal construction sites). Once, a group of men were offloading cans of tinned meat covered in foreign lettering. Some of them opened them and ate. Valentín did not, because, like many others, food that wasn’t prepared in the gitano style disgusted him, and thus he was spared the unpleasant experience of eating dog food.

When his sister died, Valentín mourned her as tradition dictated. How long this lasted I don’t remember, but I know it was for a lot longer than his spirits could bear. It was pitiful to see him all dressed in black and holed up at home, deprived of alcohol and tobacco, with no other palliative than the conviction of his mourning.

Julián

I didn’t recognise him, but he did, of course – that’s how he made his living: remembering everything and everyone. I ran into him in Seville in 1985. He was carrying himself like a Castilian nobleman trying to conceal his inner marrano (converted Jew) that his erudition and aquiline nose suggested. But then when he relaxed, he would drop the character of the squire in Lazarillo de Tormes and reveal the Jean Genet in him, the Julián of Barcelona, who was more a rascal than the university literature student he also was.

But he hadn’t fled the cold of Ávila to spend all day in the university library, but rather in the warmth of the environs of the Plaça Reial, home to so many others who found in the bustle of those streets a bewildering place that radiated light in the darkness. It is not that there was freedom in Barcelona – some homosexuals were in prison for being openly gay thanks to the Law of Vagrants and Thugs – but they had what freedom they had and they defended it with pride.

In the seventies, Julián lived in the Barrio Chino because it had stopped being a refuge for sinners and had become home to all those who wanted to live with joy and honesty. From there he moved to Seville, where he turned his ‘non-work’ into conscientious employment. Wiry, upright, not very tall, a somewhat priestly head, he cut quite a stiff figure, except for his arms, which moved constantly and sedately, as if he were about to wrap himself in the cloak of Lazaro’s squire.

He was a cultural activist. His non-work was extensive and required a lot of attention and effort. It consisted in creating a network of communication among strangers with whom he ‘democratised’ – that is, shared – the burden of his livelihood. He would turn up at my place, usually just before lunch, with a book or two under his arm: one that he would be returning and the other, borrowed from another house, would be for me to read. Later, he would leave with a book of mine. He was quite good about borrowing and returning, and in fact provided a kind of socio-cultural service, for as a reader he had exquisite taste.

We would spend many afternoons strolling along the river or through the city before winding up in a bar. I would sometimes pay for him to come with me to the cinema or to musical shows or to a bullfight, but not always as he would occasionally obtain tickets by his own means. He was an excellent conversationalist and we talked about many things, especially literature and art. That was the nexus.

He even brought into his network a member of a prominent Sevillian aristocratic family. He didn’t boast about that particular friendship, perhaps because he didn’t get out of it as much as he did from some of his regular benefactors. But he wasn’t a gossip either. He shared some of his friends with me, like Jesús and Cristo. The other way around, however, was not possible: my friends didn’t see his funny side and they didn’t value his gift of the gab or his talent for living on air enough to buy him drinks or lunch. Perhaps they hadn’t read Lazarillo de Tormes as many times as I had.

Pretending to be a sparrow in a den of vampires is not such a bad thing with people and places being what they are. When he dies he won’t leave any polluting traces: an ecological sparrow, he lived off the surplus of others and he recycled: his clothes, his books, his hat – even his exquisite leather shoes, stolen from him one night as he slept out in the open on the banks of the Guadalquivir.

White roses in the Rubió i Lluch Gardens

Beauty is the sublimation of horror: that is made clear by both art and photojournalism.

The Rubió i Lluch Gardens, inside the old Hospital de la Santa Creu, are a large courtyard with trees and flowerbeds that opens onto several streets. The gardens are closed at night, but during the day fill with a motley crew of people: students from the nearby Escola Massana, users of the Biblioteca de Catalunya, tourists and locals, who come to play chess, walk the dog or read at the small tables of this sunlit open-air library. Others can be found hidden away in recesses drinking cheap alcohol, using drugs or sleeping off their misfortune. Arguments, loud voices and unpleasant odours are smothered by the intoxicating smell of marijuana. Orange trees and jacarandas, and white roses in flower- beds; wild roses with scant petals in symmetry with their surroundings, their delicate petals dropping at the slightest breeze. Not long ago, the flowerbeds near Carrer Hospital were removed, leaving these gardens all but mutilated. Gone are the reflection of my joy or my heavy heart that used to comfort me at the beginning and end of my day at the school where I work.

In the seventies, I used to live near those fluffy white roses that so caught my attention. The relevance of whether or not their stems had thorns was blurred by so many needles pricking arms. But then, as now, I would see in those white roses the image of human fragility, of our frustrated desires and inherited injustices.

Dog roses, wild rose bushes, girls, boys, women and men, humiliated and downtrodden. White roses that laid bare the red of the blood.

Rain

There are some places where rainfall does not clean. I am really not sure that it does in the Raval, for example. There, the balconies double as storage space for ambiguous-looking objects left exposed to the elements, to pigeons and to grimy pollution. They are even used as space for leaving rubbish when it is not taken down to the bin, which is why, whilst waiting, I tried to avoid the rainwater that dripped from above. The café where we had arranged to meet was still closed, so I stood in the shelter of a tiny doorway, wary of the murky raindrops falling around me.

And if you stepped on a broken or loose paving stone (and there are plenty of them), your leg would get spurted with a dark filthy liquid – ugh! I moved to one side. Two youths scurried past, oblivious to the rain and to me. They oozed energy – and violence: they embodied it and they irradiated it.Though they didn’t touch me, I sensed the vigour in their steps, their single-mindedness, their strength and their youth all offered up to life. And I said to myself: Look at you, waiting here, lost in thought. You think that because we all breathe this foul air we all belong to this hostile place; but no, be in no doubt: fortune looks different depending on where you stand.

‘Are they off to the metro to pick pockets?’ But my question was misguided because wherever it was they were going, that moment, as they walked and chatted and laughed, was entirely theirs: it belonged to them – and they hadn’t stolen it from anyone.Winter

The same dark alleys, the same filthy corners. Overcrowded families? Yes. Abandoned? Also. A patch of sky at the top of a well that throws down a grey light onto the people living below: this is the Raval. Pockets of enduring deprivation and tourist flats, side by side. Poverty has always appealed to tourists with its characteristic colours and patterns – and because it shows a frightening truth that doesn’t affect them. Kernels of misery exist alongside splendid buildings and transparent occupants. But at certain times these same streets also turn into the natural habitat of clients on the hunt for all sorts of goods and services.

No daylight, pinched electricity and no toilets. No running water either? Presumably not. Why are youngsters filling plastic jerry cans with water from the fountain in Plaça del Pedró at sunrise if there is? Is water so expensive? Or is it that it doesn’t reach the squats, which offer only the shelter of walls and a roof?

Every morning you see wheelbarrows and big jerry cans being carted around by sleepy youngsters. Why would they do that if their homes had water? Pulleys hang from these tall buildings to raise and lower items and thus get around the problem of the narrow streets and steep stairs. But the dead – how do they come down? Whenever is convenient and under the cover of night. Rubbish continues to pile up in every corner, and in the early hours, you see cockroaches scuttling back into their hiding places. They don’t like the light – nor do rats.